Don Castro's Outlaw Justice - Part One

Posted by Norm DeWitt, Motorcyclist Magazine on Jul 16th 2018

Triumph's 750cc twin was the weapon of choice for the 1972 AMA Grand National Championship. Housed in custom steel skeletons built by Trackmaster, Red Line or C&J; a typical example might weigh 290 points and make upwards of 70 horsepower. Don Castro's Red Line-framed Triumph wasn't your typical Triumph 750 flat tracker. Neither is the story of the birth, death and ultimate resurrection of the bike that could have changed everything.

The kid from Hollister, California turned Pro at 18, hit the big-time in 1969 and won seven Junior Nationals in his rookie year. Triumph racing boss Pete Coleman was suitably impressed, signing Castro to the factory team in '70. Spectacular talent, hard work and meticulous attention to the mechanical details earned Castro fifth place in his first year as a card-carrying Pro. But as he finished his second Grand National season in ninth, Triumph was sinking in a rapidly rising tide of superior Japanese street machines. Hard times at the home office meant harder times for the race team. Both Castro and Gary Nixon were cut. "That was when I turned privateer," Castro says. "Triumph was bankrupt and we were out on our own."

After a bad start, '72 was about to get worse. "Everything got ripped off while on the way to the Houston Astrodome," Castro says. "I went to Gardena to get some braided brake lines. When I walked back outside, my van was gone, along with my Trackmaster Triumph TT bike and my Montesa. They cleaned me out!" Almost: Castro had a Red Line-framed Triumph in his garage back home that could salvage the season.

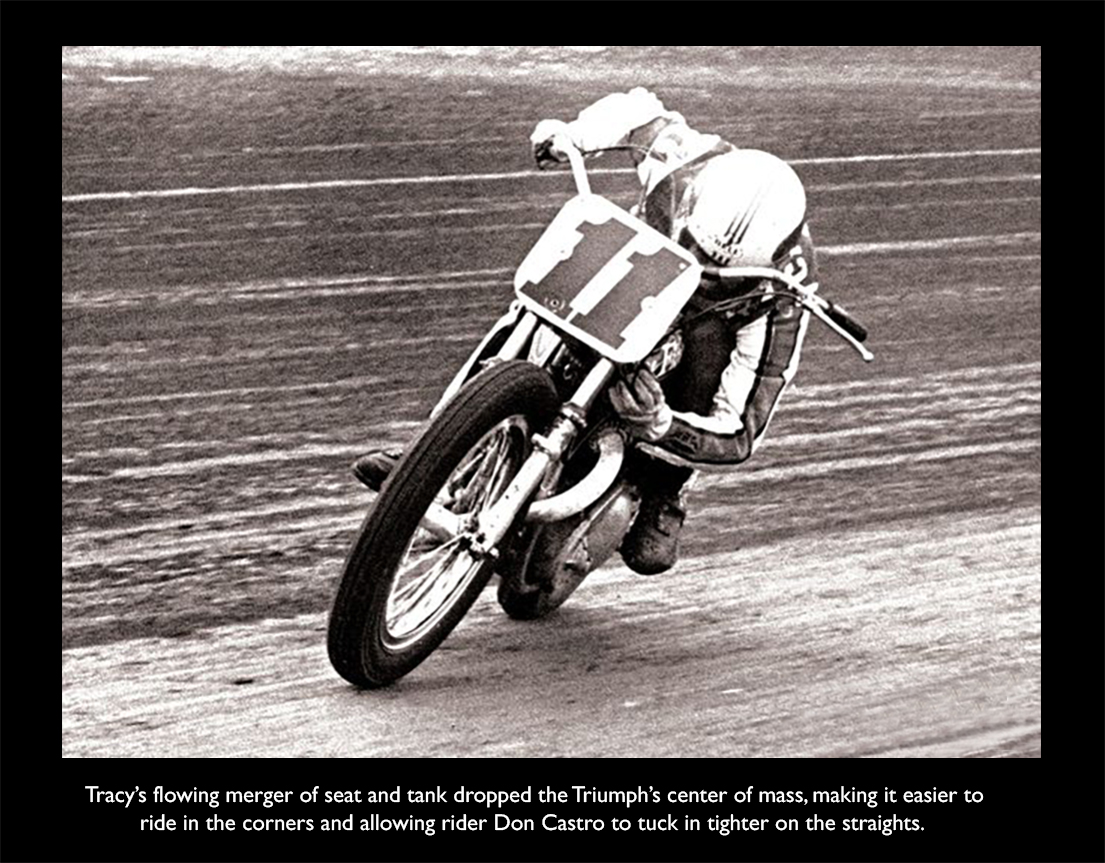

By June, Castro had gotten some help from Tracy Nelson of The Fiberglas Works in Santa Cruz, California. The Grand National paddock's artist-in-residence laid up something new for the Triumph, just in time for the Race of Champions half-mile at San Jose. Tracy united the seat, fuel tank and side numberplate in one flowing piece, adapting an aerodynamic pannier-style tank design used by the AJS factory road racers in the early '50's. "Tracy and I designed it so the air would flow smoother, but we also lowered the center of gravity," Castro says. "All the weight was really low, so handling was perfect." With the fuel riding six inches lower than a conventional set-up, Castro could tuck in tighter than anyone else. Psychedelic '70's graphics attracted even more attention.

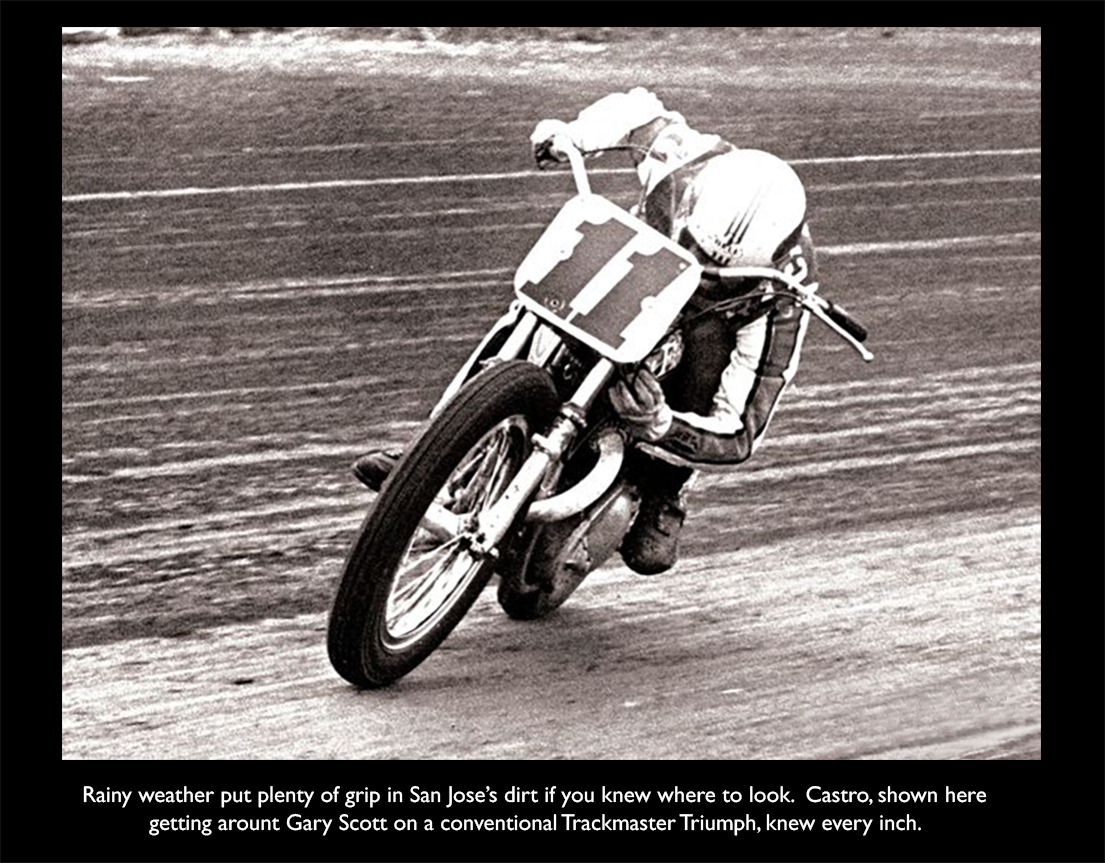

Castro wasn't eligible for the Race of Champions - his first National win as a car-carrying Pro would come a year later on the same track - but he dominated every race he lined up for that day in the slippery new Triumph's first and last appearance. Aerodynamic assistance was against the rules, but the line between a permissible seat/tank/numberplate combination and illegal streamlining seemed open to interpretation until Castro and Tracy crossed it and the AMA officials pronounced the bodywork illegal. The rest of the bike would be fine with the previous conventional setup, but it really didn't matter as Castro had signed to team with Kenny Roberts on Yamahas for '73. "I sold the Triumph to a school teacher who raced it a few times and that was the end of it," he remembers.

Or so he thought. Looks for Part Two to find out how Don Miller resurrected the infamous Triumph.